The Peoples of Lenapehoking

Lenape, meaning “People” or “Original People”, is the name of the Native and Indigenous peoples who built vibrant and diverse cultures and livelihoods along the mountain ridges and waterways of this region for centuries before European colonists settled in Turtle Island (North America).

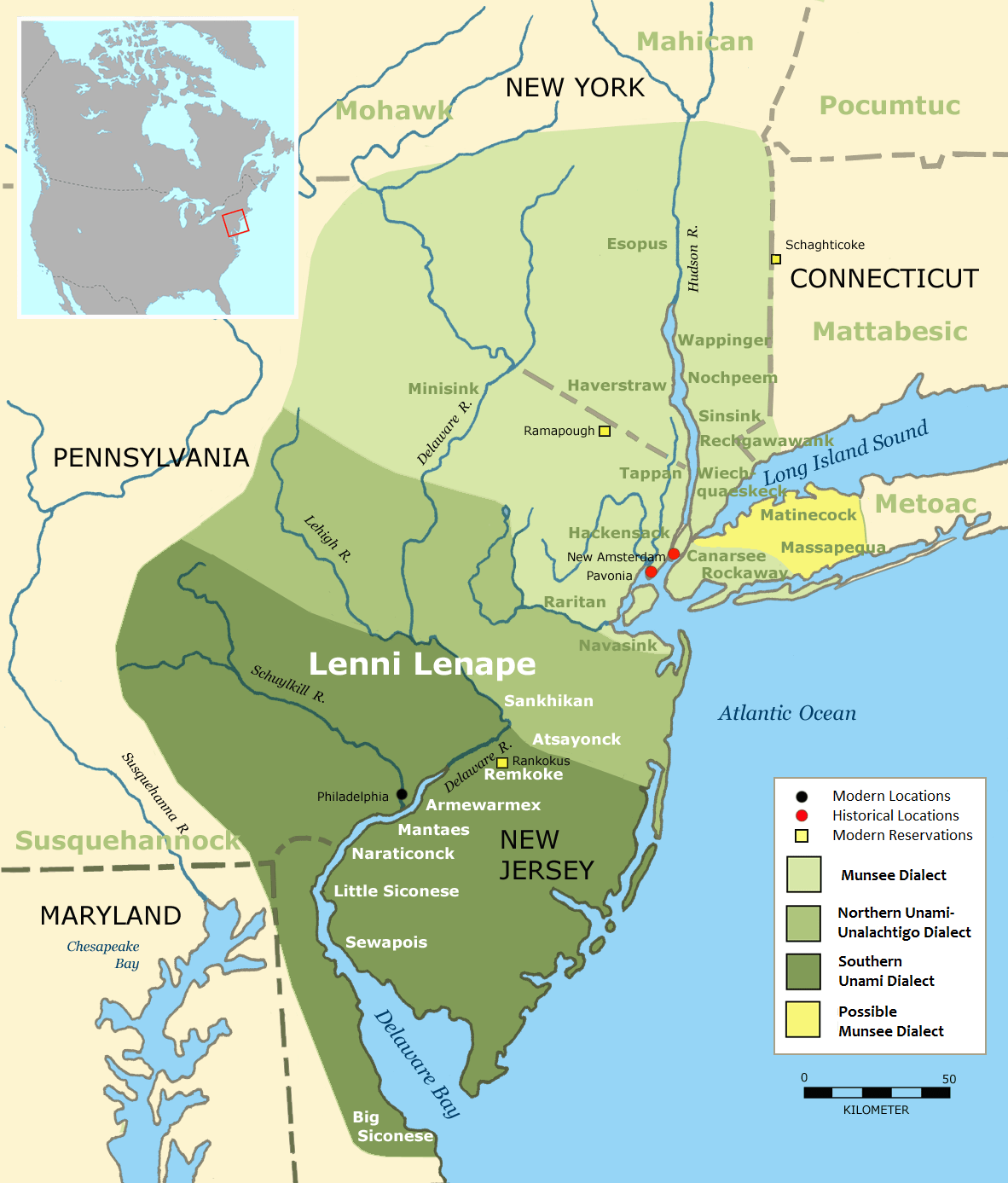

Lenapehoking, homelands of the Lenape, stretches from the present-day border of western Connecticut, across the lower Catskills and mid-Hudson region to eastern Pennsylvania, south through New Jersey and western Long Island, and southwest to Delaware Bay.

Caption: This map shows the approximate boundaries of Lenapehoking along with regional dialects spoken by diverse Lenape communities. For example, the lightest shade of green to the north indicates the homelands of Munsee-speaking Lenape peoples like the Esopus. Source: https://native-land.ca/maps/languages/delaware/

Here and around present-day Kingston, New York are lands of the Esopus, a Munsee-speaking group of Lenape peoples. Esopus derives from the Munsee word shiipoosh meaning “little river”. Like their relatives, the Wappinger, whose lands are in the Hudson Highlands along the Mahicannituk (Hudson River), the Esopus lived in community villages where they planted culturally-important crops like squash, beans, corn, tobacco, and sunflowers. These semi-permanent agricultural villages were organized by extended family kinship or clan systems. The Esopus and other Lenape relatives also utilized seasonal camps for hunting, fishing, and harvesting of shellfish, nuts, tubers, berries, and other edible and medicinal plants. The Lenape developed their diverse and evolving cultures and livelihoods, and maintained relationships with other Native peoples nearby, over many millennia until the violent disruption of European colonization.

Contact between Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island (North America) and European settler-colonists was not coincidental. The stage was set in the 15th century by the Doctrine of Discovery, a legal, political, and religious framework that empowered European Christian explorers, in the name of their monarchs, to seek and lay claim to lands unoccupied by Christians. For these European nations, the Doctrine of Discovery legalized the seizing, exploitation, and settlement of lands around the world, the attempted genocide of the peoples inhabiting them, and the trafficking and enslavement of Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island and of West & Central Africa. It is in this context Dutch colonists made their way to Lenapehoking to develop trade and settlements in the 17th century.

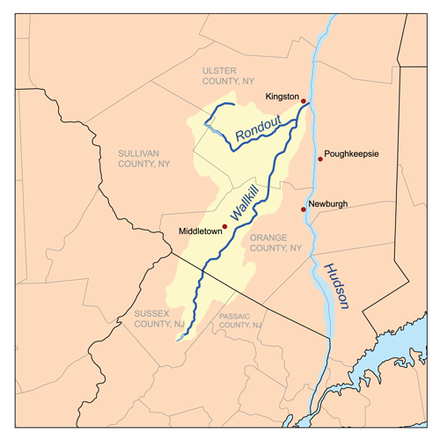

From 1609-1664, the Dutch West India Company and the colony of New Netherland took control of portions of traditional Lenape lands along the Mahicannituk. The lands of the Esopus, located halfway between the settlements of Fort Orange (present-day Albany) and New Amsterdam (present-day New York City), became a strategic location for the Dutch in terms of trade and battle with the Lenape. Here, in 1652, they established the settlement of Esopus, later renamed Wiltwyk. Further inflamed by the establishment of Wiltwyk, conflict between the Dutch and the Esopus rose to war in 1659 and 1663. The Esopus Wars, as they are known, were brutal on all sides, and ended with a treaty that formally displaced the Esopus from more of their ancestral lands. The Dutch, weakened from fighting, were left vulnerable to competing European nations, and in 1664 ceded their territory to the British. Wiltwyk of New Netherland became Kingston of New York.

Caption: This map shows the location of Kingston, New York near the confluence of the Mahicannituk (Hudson) and the Rondout Creek.Source: https://www.clearwater.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/Section-2-Rondout-Creek-and-Adjacent-Watersheds-12_30.pdf

European colonization, followed by the Revolutionary War and establishment of the United States (US), resulted in the forced displacement of the majority of Esopus and their Lenape relatives from Lenapehoking. Most Lenape were gradually displaced as far west as Oklahoma and as far north as Wisconsin and Ontario, Canada. Today, there exist three Lenape communities recognized by the US government and three First Nation Lenape communities recognized by the Canadian government. There are also a number of state recognized Lenape communities, and a Lenape diaspora of communities and individuals who claim Lenape heritage. About 20,000 people self-identify as Lenape today.

More information about Lenape communities today can be found on their respective websites, which can be accessed through native-land.ca.

Living Land Acknowledgement

The Doctrine of Discovery was upheld by the United States Supreme Court as recently as 2005, and Native, Indigenous, and First Nation peoples across Turtle Island continue to fight for sovereignty of their ancestral lands today. The Kingston Land Trust, with the support of the Lenape Center, has developed this living land acknowledgement as a part of our commitment to land justice and solidarity with Indigenous peoples. Organizations like the Lenape Center, located in present-day Manhattan, are working with Native and non-Native people to strengthen Lenape presence and voice in Lenapehoking.

The Kingston Land Trust acknowledges that we occupy and hold title to land that was violently taken from the original stewards: Esopus peoples of Lenapehoking. As a land trust, we consider land our sacred and collective heritage, and we find our purpose in the protection, access, and stewardship of that heritage. To do so in alignment with our commitment to justice requires us to confront the truths of Indigenous land dispossession, displacement, and attempted genocide and erasure. We acknowledge that these grave injustices continue and are the reasons why many of us as non-Native peoples can exist here today. Therefore, the Kingston Land Trust understands that justice for, and solidarity with, Esopus and Lenape peoples must be central to our organization’s purpose and work.

We acknowledge the native plants and animals, waters, and lands that make up Lenapehoking as living relatives of the Lenape. We affirm the ancestral relationships and responsibilities Esopus and Lenape peoples have to their relatives, and we are committed to building respectful, reciprocal, and reparative partnerships with Lenape peoples, so that those relationships and responsibilities may be upheld. More broadly, the Kingston Land Trust looks forward to exploring the various ways we can support the rematriation of land both locally and regionally, and honor the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples in the past, present, and future of Turtle Island.

Industrial History and Urban Renewal

The Rondout neighborhood, where this forest sanctuary is located, helped fuel the industrial development of Kingston through the transport of coal from Pennsylvania on the Rondout Creek (via the Delaware and Hudson Canal). The local limestone formation, which extends south to Rosendale and north to the Town of Ulster, was mined for natural cement on the land that is Hasbrouck Park today. By circa 1855, the Newark Lime and Cement Company became one of the leading manufacturers of natural cement in the country. Circa 1860, German immigrant Frederick W. Gross developed a quarry on Delaware Ave that manufactured ground lime in a mill on Hasbrouck Avenue near Murray Street. The Rondout & Oswego Railroad (reorganized into The Ulster & Delaware Railroad in the 1870s) was built starting in 1868 under the leadership of Thomas Cornell and carried freight such as agricultural products, lumber, bluestone from the Catskills, Kingston products such as bricks and cement, and Pennsylvania coal from the D&H canal. There was also passenger service between Kingston and the Catskills that later connected to the steamboats and dayliner at Kingston Point and took travelers to hotels in the Catskills. This is the railroad bed that was converted into the Kingston Point Rail Trail in 2019 and runs along this Forest Sanctuary.

During the 1920’s, the City of Kingston purchased land from the Abraham Hasbrouck family and from the Newark Lime and Cement Company to establish Hasbrouck Park. The Kingston City School District received title to part of the park in 1946 and built a new school (JFK) in the early 1960’s to replace #3 School that was on Chambers Street and was taken down during Urban Renewal. Urban Renewal was the federally funded 1960s project to “eliminate substandard and deficient areas and transform them into standard ones” that destroyed nearly 500 buildings and displaced thousands of people, many of them Black folks who had difficulty finding new housing. Rondout Gardens public housing was built during this period, and some of the thousands of people displaced by the Urban Renewal’s demolition of nearly 500 buildings moved here.

Ecology

To help define ecology, we can first look to Movement Generation’s definition of ecosystem:

Ecosystem means all the relationships in a home—from microorganisms, plants,

animals and people to water, soil and air. An Ecosystem includes the terrain

and the climate. An Ecosystem is not simply a catalogue of all the things that

exist in a place; it more importantly references the complex of relationships. An

ecosystem can be as small as a drop of rain or as large as the whole planet. It all

depends on where you draw the boundaries of home.

-- Movement Generation, Just Transition Booklet, 2016

If ecosystem refers to the relationships in a home, then ecology refers to knowing and understanding those relationships of home. At the Kingston Land Trust, we aim to help develop a collective ecological knowledge, in partnership with the land, human communities, and more-than-human communities, towards ecological and social well-being for all. To do so requires us to understand ourselves as interwoven with the rest of life rather than separate: ecological well-being is social well-being. In fact, as long as humans have existed, we have shifted and shaped the ecosystems we live in, just as we have been shifted and shaped by those ecosystems. Through this dance, humans have learned from the earth and developed cultures that practice balance and mutual benefit, towards thriving ecosystems that support thriving human communities.

Unfortunately, in more recent human history, cultures that practice the exploitation and extraction of earth materials and human labor towards private accumulation of land, power, and wealth have upended many of the traditional relationships between humans and the rest of life on earth. Here along the Mahicannituk (Hudson River), across Turtle Island (North America), and around the world, European colonization initiated a period of severe disturbance to the land, including intensive farming, grazing, mining, and urbanization, meanwhile displacing Indigenous nations and peoples from their ancestral lands through violence, enslavement, and attempted genocide. Subsequently, globalized economies designed to expand these exploitative and extractive industries have been allowed to flourish. Colonization and globalized economic systems have also shifted and intensified human migration across continents, resulting in the introduction of plants, animals, viruses, and more that were not found prior, and who can easily adapt to disturbed landscapes.

Ultimately, the extraction and exploitation of land, and the displacement of human and more-than-human beings, has had a significant impact on biodiversity, ecosystem health, climate stability, and overall well-being of life on earth. Our global ecosystem and climate are at a crossroads, and the future of our home depends on how we continue to treat and relate to the earth and each other.

Stewardship

As land stewards today, we must remember how to practice balance and mutual benefit towards thriving ecosystems and communities. Central to this work is building respectful, reciprocal, and reparative partnerships with the original stewards of the land. The Kingston Land Trust acknowledges that the Forest Sanctuary exists on lands that were violently taken from Esopus peoples of Lenapehoking, just as we recognize that the United States was built largely on the backs of enslaved African peoples. We look forward to exploring how we can support land rematriation and land sovereignty for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), as well as how we can collaborate with Esopus, Lenape, and BIPOC community members to steward land together in the spirit of solidarity and healing.

It is also our responsibility as land stewards to be thoughtful in our relationships with the diverse more-than-human communities we share space with. Biodiversity is a core principle by which nature builds ecological resilience against disruption, so in our efforts to heal historic land disturbance, a priority is to enhance biodiversity. Sometimes, this means limiting the spread of certain plants that significantly minimize biodiversity, such as those who have been introduced to these landscapes without native predators to keep them in balance. At other times, this means encouraging a mixture of native and introduced plants that can offer mutual benefit, thereby challenging the assumption that all introduced plants are inherently “bad” or dangerous. Ultimately, we want to act in ways that honor the gifts of all beings, that promote cooperation and diversity, that consider what we do not know or cannot see, and that support the earth’s ability to heal and regenerate. The Kingston Land Trust looks forward to working with you and our partners to further articulate our practices and overall philosophy of land and ecological stewardship.

Forest Diversity and Disturbed Land

When the KLT first began stewardship here in 2019, the forest was “early successional” and mostly made up of tree species that were able to grow fast and thrive after disturbance, dominated by Norway maple and a smaller number of bigtooth aspen. There were also smaller numbers of Catalpa, White Mulberry, Black Walnut, and Wild Cherry. This lack of species diversity was a reflection of a history of disrupted Indigenous relationships with the forest and extractive land use like clear cutting and mining.

The understory was also mostly made up of non-native (introduced) species able to thrive in disturbed land that spread vigorously, such as: Japanese Barberry, Asian Honeysuckle, Wineberry, Garlic Mustard, Japanese Knotweed, Ailanthus, and Oriental Bittersweet). There were also native species in the understory, such as (Jewelweed, Bloodroot, Snakeroot, Black raspberry, Virginia Creeper, and Poison Ivy).

There were just a few individual plants that are more characteristic of mature mid-to-late successional forests in this region, such as basswood and sugar maple trees, spicebush, and ferns‒all species that Indigenous communities have long-standing relationships with.

To increase diversity and let light in, we thinned out many Norway maple trees, removed dead trees, and spread the wood chips throughout to build soil. In forest openings, we are continuously planting a variety of trees and shrubs, including native plants that offer sweet foods and medicines (photos of Sassafras, Pawpaw, Elderberry). We also planted a Community Food Forest!

As land stewards, we are working to mend historical land disturbance by supporting the transition of the forest toward greater maturity, biodiversity, ecological resilience, and edible abundance. We plant and encourage native and edible plants and limit the spread of certain non-native species that can otherwise dominate a landscape while still acknowledging the functional roles and gifts of all plants. Ultimately, we seek to act in ways that consider what we do not know or cannot see and support the Earth’s own ability to heal and regenerate. We also hope this site will offer a place for learning, creativity, play, healing, and refuge, along with sweet foods and medicines in abundance.

We would love to hear your thoughts about land stewardship and to steward this land alongside you! Contact us at landstewardship@kingstonlandtrust.org with feedback and to learn about how to get involved.